An investigative report by Small Newspaper Group

Illinois lacks investigators, background on teachers before 2004

By Scott Reeder, Small Newspaper Group

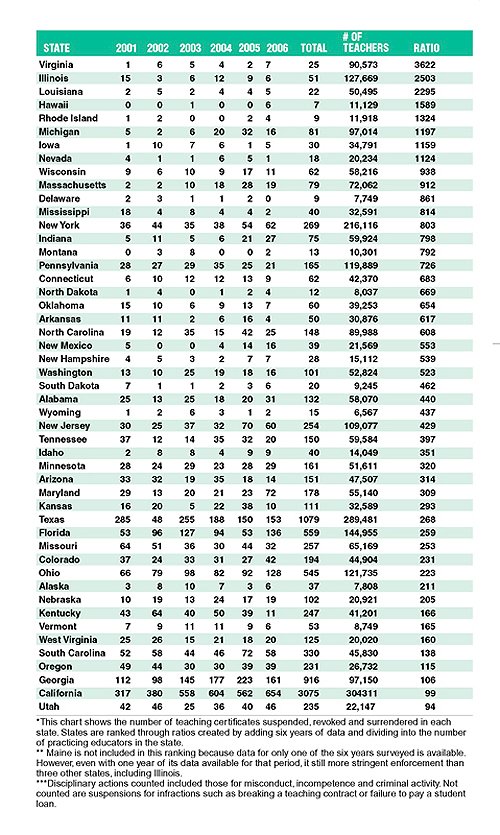

SPRINGFIELD -- Most teachers are committed to helping children learn and protecting them from harm, but like any profession there are a few wormy apples. Some states are willing to put up with more worms than others. To find out how Illinois compares, Small Newspaper Group filed open records requests with 50 state education departments and built a national database of revocations and suspensions of teacher licenses. Only Virginia revokes or suspends fewer teaching certificates than Illinois. The disparities between states are startling. For example, states such as California, Georgia or Utah are 25 times more like to remove a teacher from the profession than Illinois. Unlike most states, neither Virginia nor Illinois have staff investigators to follow up on complaints against teachers.

``I definitely believe there should be investigators. School administrators are not trained to be investigators so they wouldn't do a good job. I would like to see state investigators, that whenever there was an allegation they would come right out,'' said Charol Shakeshaft, a national expert on sex abuse in the schools and the chair of Virginia Commonwealth University's education department. Mary Jo McGrath, a California lawyer specializing in teacher misconduct cases, said she believes the differences in suspension and revocation rates between states reflects differences in how vigilant states are in protecting students. ``I lecture on teacher misconduct issues all across the country. I don't believe that a teacher in one state is more prone to bad conduct than in another,'' she said. But there are differences in how aggressively states conduct background checks on teachers. In 2004, State Rep. Careen Gordon, D-Morris, introduced legislation that would require all teachers to be fingerprinted and undergo a national background check. The state's two teacher unions immediately objected. Rep. Gordon, who prosecuted sex offenders for the Illinois Attorney General before becoming a lawmaker, said she was surprised by the union reaction. ``Their response was basically, `why are you picking on us?''' she said. Both the Illinois Education Association and the Illinois Federation of Teachers also expressed concern about the logistics and cost of fingerprinting 127,000 teachers. ``I think if someone has been serving honorably in a school district for 25 or 30 years or even longer the idea that they should take time out their day to be fingerprinted doesn't make a lot sense from any perspective,'' said Charlie McBarron, spokesman for IEA. The compromise bill, which passed in 2004, only requires fingerprinting for teachers when they are first hired by a school district. That means most teachers hired before 2004 have not undergone a complete criminal background check and likely will not for the remainder of their careers. Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart contends this approach is a mistake. He noted that some teachers hired before 2004 may continue to be in the profession for 30 or more years. ``That means we won't know until 2034 whether there are teachers with something in their background that should be known,'' he said. ``I just scratch my head and say, why? No one is being accused of anything wrong, it's just a process that we do all the time for all sorts of different professions that come in contact with kids.'' Before becoming sheriff, Dart prosecuted child sex crimes for the Cook County State's Attorney's Office and served as a state legislator. There is a danger of becoming overly reliant on fingerprinting, said Carolyn Angelo, executive director of the Pennsylvania Department of Education's Professional Standards and Practices Commission. ``Fingerprinting is just one tool -- a snapshot in time,'' she said. If it is just done when a teacher enters the profession, it's obviously not going to tell you about problems the teacher may have after being hired, Angelo added. ``One proposal made here in Pennsylvania was to have teachers fingerprinted every year -- that would really have the teacher unions up in arms,'' she said. Maine began the process of fingerprinting all of its teachers in 2000. Angus King, who was Maine's governor at the time, said it was the most controversial matter during his time as governor with some teachers contending fingerprinting violated their civil rights or impugned their character. Teachers resigned in protest, held candlelight vigils, testified before legislative committees and labeled the initiative the ``Prints of Darkness.'' ``To me exempting existing people in the system is really not getting at protecting kids, which this is all about,'' Gov. King said. ``The unfortunate reality is that in a large group of people you will have people who are prone to do bad things. I view it as a minor inconvenience to a lot of people in order to prevent a horrendous life-changing trauma to a few people.'' Sheriff Dart shared former Gov. King's point of view. ``You should do it completely,'' Sheriff Dart said. ``It's not besmirching anybody. There's nothing humiliating about it. People who will say that it's a humiliating process to get fingerprinted. I'd just tell them, you've done nothing wrong, but in an effort to ensure that our schools are safe we have to do this for everybody.''

``I definitely believe there should be investigators. School administrators are not trained to be investigators so they wouldn't do a good job. I would like to see state investigators, that whenever there was an allegation they would come right out,'' said Charol Shakeshaft, a national expert on sex abuse in the schools and the chair of Virginia Commonwealth University's education department. Mary Jo McGrath, a California lawyer specializing in teacher misconduct cases, said she believes the differences in suspension and revocation rates between states reflects differences in how vigilant states are in protecting students. ``I lecture on teacher misconduct issues all across the country. I don't believe that a teacher in one state is more prone to bad conduct than in another,'' she said. But there are differences in how aggressively states conduct background checks on teachers. In 2004, State Rep. Careen Gordon, D-Morris, introduced legislation that would require all teachers to be fingerprinted and undergo a national background check. The state's two teacher unions immediately objected. Rep. Gordon, who prosecuted sex offenders for the Illinois Attorney General before becoming a lawmaker, said she was surprised by the union reaction. ``Their response was basically, `why are you picking on us?''' she said. Both the Illinois Education Association and the Illinois Federation of Teachers also expressed concern about the logistics and cost of fingerprinting 127,000 teachers. ``I think if someone has been serving honorably in a school district for 25 or 30 years or even longer the idea that they should take time out their day to be fingerprinted doesn't make a lot sense from any perspective,'' said Charlie McBarron, spokesman for IEA. The compromise bill, which passed in 2004, only requires fingerprinting for teachers when they are first hired by a school district. That means most teachers hired before 2004 have not undergone a complete criminal background check and likely will not for the remainder of their careers. Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart contends this approach is a mistake. He noted that some teachers hired before 2004 may continue to be in the profession for 30 or more years. ``That means we won't know until 2034 whether there are teachers with something in their background that should be known,'' he said. ``I just scratch my head and say, why? No one is being accused of anything wrong, it's just a process that we do all the time for all sorts of different professions that come in contact with kids.'' Before becoming sheriff, Dart prosecuted child sex crimes for the Cook County State's Attorney's Office and served as a state legislator. There is a danger of becoming overly reliant on fingerprinting, said Carolyn Angelo, executive director of the Pennsylvania Department of Education's Professional Standards and Practices Commission. ``Fingerprinting is just one tool -- a snapshot in time,'' she said. If it is just done when a teacher enters the profession, it's obviously not going to tell you about problems the teacher may have after being hired, Angelo added. ``One proposal made here in Pennsylvania was to have teachers fingerprinted every year -- that would really have the teacher unions up in arms,'' she said. Maine began the process of fingerprinting all of its teachers in 2000. Angus King, who was Maine's governor at the time, said it was the most controversial matter during his time as governor with some teachers contending fingerprinting violated their civil rights or impugned their character. Teachers resigned in protest, held candlelight vigils, testified before legislative committees and labeled the initiative the ``Prints of Darkness.'' ``To me exempting existing people in the system is really not getting at protecting kids, which this is all about,'' Gov. King said. ``The unfortunate reality is that in a large group of people you will have people who are prone to do bad things. I view it as a minor inconvenience to a lot of people in order to prevent a horrendous life-changing trauma to a few people.'' Sheriff Dart shared former Gov. King's point of view. ``You should do it completely,'' Sheriff Dart said. ``It's not besmirching anybody. There's nothing humiliating about it. People who will say that it's a humiliating process to get fingerprinted. I'd just tell them, you've done nothing wrong, but in an effort to ensure that our schools are safe we have to do this for everybody.''

Copyright ©2007 Small Newspaper Group

Quad-Cities Online Moline & Rock Island, IL |

MyWebtimes.com Ottawa & Streator, IL | Daily Journal Kankakee, IL |